Much of the information in this profile uses John Canemaker's interview with Emery Hawkins, intended to research his book The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, as a primary source, unless otherwise noted. This is part one in a series of three posts.

Emery Otis Hawkins was born April 30, 1912, in Jerome, Arizona, to Charles Thomas Hawkins and Frances Elizabeth Bruce.1 Hawkins remembered that his hometown of Jerome “was on the side of a mountain, and it was honey-combed with mining shafts.” He and his family moved from Jerome to Cottonwood, then to Camp Verde, before settling in Stonewood Lake. For two years, Emery’s father, Charles, was “the all-around cowboy” of Arizona. “Roping, riding, throwing, everything, all of it,” Hawkins explained. “Trick roping, everything. He could play a fiddle and jig and call a dance all at once. He had been a dairyman and a cattleman, done all that.”2

1910s postcard of Jerome, Arizona.

Hawkins began drawing at two years old, like many young children his age. His mother, Frances, shared his artistic nature, being a painter herself. The other side of his family— ”aunts and things”—also immersed themselves in music and painting. Frances separated from her husband, taking her young son out West to California. On October 11, 1919, Frances remarried to Fred E. Taylor in Los Angeles, relocating to San Diego by 1920.3 A cabinetmaker by trade, Fred “made everything of his own in the days when you couldn’t go out and buy all-electric tools...made all his own, put his motors up, made babbitt bearings for the shafts.”

Hawkins’s love for drawing continued, with his first published work appearing in the Los Angeles Times cartoon section at age 14.4 Hawkins received an education at Fremont “some of the time,” then transferred to North Hollywood High. Meanwhile, the monumental success of Walt Disney’s new sound picture Steamboat Willie inspired many budding artists nationwide to pursue a career working in animated cartoons. The young Hawkins had already dabbled in animation on notebooks and flipbooks. “I had a desk before I ever saw the inside of a studio,” he said. The sixteen-year-old had animated a scene of a clown walking and dancing to prove his capabilities to Disney. “I couldn’t get past the door. They said, ‘We don’t want copy work.’ They didn’t think I did it.”

After graduating high school, Hawkins took his first animation job, starting at Walter Lantz’s studio as an inker. This stint only lasted a couple of months. “I changed all the cels because I didn’t like the way it was animated, so they canned me.” Rearranging the animation during the ink-and-paint process launched a series of mildly subversive acts that would become characteristic of Hawkins throughout his career. Hawkins was aware of this side of his behavior, stating frankly, “Actually, I’ve always been kind of a renegade in the business.”

Charles Mintz’s studio produced cartoons featuring Krazy Kat and Scrappy, distributed by Columbia Pictures. Hawkins entered there as early as 1932, working alongside veteran animator Dick Huemer on the Scrappys.5 The timing was fortunate since Hawkins could bypass the position of in-betweener and assistant. “[Huemer] supposedly was going to have me work on stuff, but he wanted to leave. So, he’d come in the morning and make some drawings and give them to me and he’d put one drawing on the board, turn the light out and kill the day, and I’d animate. After a couple of months, I was a regular animator.”

Shortly after, the studio went into a state of turmoil. The chief animator-directors Huemer, Sid Marcus, Ben Harrison, and Manny Gould participated in a walkout over a salary dispute between Mintz and Columbia.6 Mintz disregarded their demands and granted the remaining artists a promotion in their absence. “[He] turned to all the young guys that were there and said, ‘Look, you’re animators.’ So we all started animating.” After a failed negotiation with Columbia, Huemer left Mintz to work for Disney while Marcus, Harrison, and Gould returned back. Many newly promoted animators returned to assisting, but Hawkins’s status remained intact—he officially became a full-fledged animator.

A short time later, Hawkins left Charles Mintz, regaining his chance to work for Walt Disney. Upon his entrance, he sat next to a young artist named Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman.7 However, Mintz contacted Disney and threatened to raid Disney’s animators if they kept Hawkins. Ben Sharpsteen, supervisor of a unit of trainee Disney animators during the early 1930s, informed Hawkins that Mintz was “raising hell.” Emery was forced to leave Disney after only a few days and returned to Mintz. In later years, Hawkins strikingly did not resent Mintz for the maneuver: “[Mintz was] actually a nice person. I mean they broke me in, gave me the opportunity and I owed them something.”

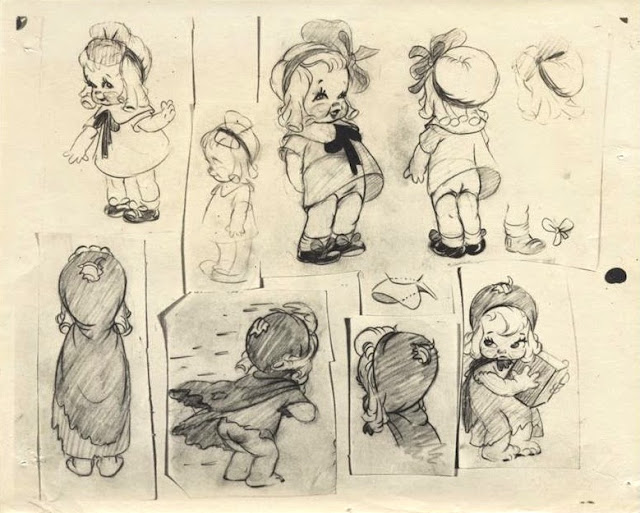

Hawkins continued to sharpen his skills at Mintz, animating on cartoons directed by Art Davis and others by Sid Marcus. Then, in 1934, Mintz decided to bring color into his cartoons, introducing a series of Color Rhapsodies. (Due to Disney’s exclusive rights to three-strip Technicolor, the early Rhapsodies were filmed in the two-color process; two-color used red and green color separations, not allowing a full spectrum of hues, compared to Disney’s Silly Symphonies. However, by 1936, Disney’s contract with Technicolor had expired, and the Rhapsodies were permitted to use the full three-strip color process.)

Hawkins also animated on a series of Technicolor cartoons featuring Billy De Beck’s popular comic strip character Barney Google, each directed by Marcus, released in 1935 and 1936. Today, these cartoons only survive in black-and-white home movie extracts and redrawn colorizations, without sound, due to King Features’ decree for the film studios to destroy any adaptation of their properties after a ten-year period. One of the most notable Color Rhapsodies with Hawkins’s involvement was Art Davis’s The Little Match Girl (released November 1937); its daring retelling of the story earned the film an Academy Award nomination.

Compilation of scenes animated by Hawkins at Charles Mintz’s studio. Clips from: LET’S RING DOORBELLS (Art Davis/1935), SCRAPPY’S BOY SCOUTS (Art Davis/1936), A BOY AND HIS DOG (Sid Marcus/1936), MOTHER HEN’S HOLIDAY (Sid Marcus/1937), SCARY CROWS (Sid Marcus/1937), THE AIR HOSTESS (Sid Marcus/1937), THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL (Sid Marcus/1937), THE FOOLISH BUNNY (Sid Marcus/1938), WINDOW SHOPPING (Sid Marcus/1938). Also included are excerpts from three Barney Google cartoons, each directed by Sid Marcus: TETCHED IN THE HEAD (1935), PATCH MAH BRITCHES (1935), and SPARK PLUG (1936). Since these cartoons only survive in silent versions, an instrumental piano cover (by Marion Abbott) of the hit 1920s tune “Barney Google” plays as accompaniment. Thanks to Mark Kausler for his input.

In the summer of 1937, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) terminated its contract with producer-directors Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising, and constructed an animation department of their own. Metro arranged plans to produce a series of 13 cartoons based on Rudolf Dirks’ comic strip, The Captain and the Kids.8 By October 15, MGM had hired a large staff of directors, storymen, animators, layout, and background artists for their new animation division.9 A few days later, The Film Daily announced Hawkins’s arrival, along with two other animators, Ray Abrams and Leonard Sebring.10

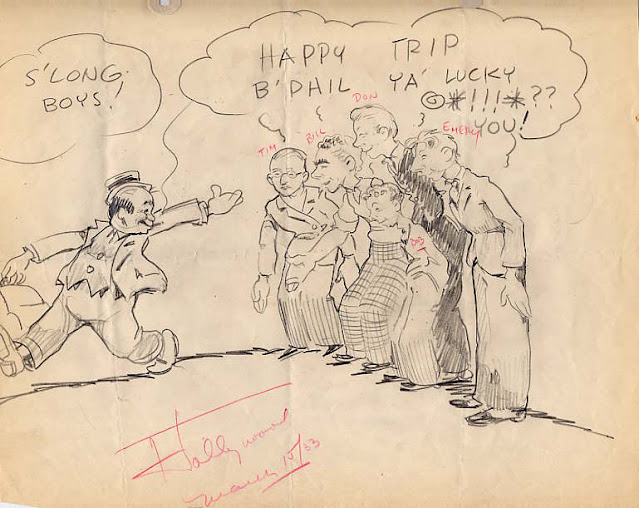

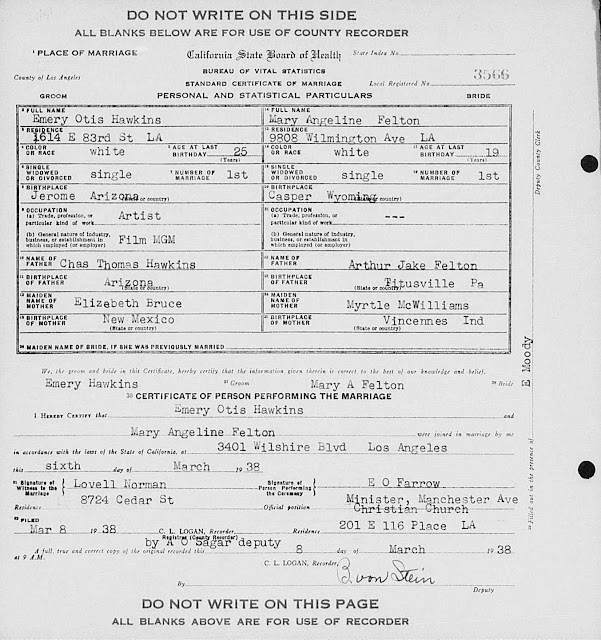

While at MGM, Hawkins married Mary Angeline Felton on March 8, 1938. Lovell Norman, another MGM artist, is listed as a witness in their marriage certificate. The two had previously worked together at Mintz—Hawkins personally recommended Lovell Norman for a job in animation there earlier in 1934, giving him his start in the business.12 Norman later became the chief sound editor at MGM in the forties and fifties. (Three months later, Hawkins returned the favor, listed as a witness in his friend’s marriage certificate in June 1938.13)

Meanwhile, Hawkins dealt with confrontations of his own at MGM. While he enjoyed working with Freleng, he “got into a fight over his way of doing things.” Rather than supervising animators’ scenes by having them flip through their drawings—the traditional method for many—Freleng often insisted on shooting rough pencil tests and asking for revisions after viewing them.16 This working method aggravated many animators at MGM since it interfered with their deadlines and footage quotas. Displeased with Freleng’s approach to directing, Hawkins quit MGM, leaving to work for Walt Disney once again.

Scenes animated by Hawkins at MGM, in production order. Clips excerpted from POULTRY PIRATES (Freleng/1938 – prod. 5), A DAY AT THE BEACH (Freleng/1938 – prod. 10), HONDURAS’ HURRICANE (Freleng/1938 – prod. 14), PETUNIA NATIONAL PARK (Freleng/1939 – prod. 15), JITTERBUG FOLLIES (Gross/1939 – prod. 18).

____________________________________________________________________________

1 Arizona, U.S., Birth Certificates, 1880-1935. Courtesy: Ancestry. Charles and Frances’s marriage certificate, dated November 10, 1910, lists his mother as “Frances E. Bruce.”. Arizona, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1865-1972. Courtesy: Ancestry. She is otherwise listed as “Elizabeth Bruce” in Emery’s marriage certificate, dated March 6, 1938. California, County Marriages, 1850-1952. Courtesy: FamilySearch.

2 Emery's birth certificate lists Charles's occupation as a cowboy. Arizona, U.S., Birth Certificates, 1880-1935. Courtesy: Ancestry. His draft registration card, dated September 12, 1918, mentions his residence at Camp Verde in Yavapai County, Arizona, working as a “cattle manger [sic].” U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918. Courtesy: Ancestry.

3 California, U.S., County Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1849-1980; 1920 US Federal Census, San Diego, District 0251, lines 14-16. Emery and Frances’s surnames are listed as “Taylor” in the census.

4 “Taos Cartoonist Animates Life.” The Taos News, January 7, 1982. Hawkins possibly submitted his first cartoon to “The Junior Times,” a Sunday supplement in The Los Angeles Times that encouraged young children to submit fiction, poetry, and artwork. Future animators like Bob Clampett and Fred Moore regularly drew illustrations for "The Junior Times." However, in researching the “Junior Times” pages issued in 1926 (and early 1927), when Emery was fourteen years old, there is no evidence of any artwork with his signature, regardless if Emery used both Hawkins or Taylor as surnames. The 1930 census lists Hawkins’s family in Los Angeles, with a Herman C. Platt as an occupant living in their residence. Again, Emery’s last name is noted as “Taylor.” 1930 US Federal Census, Los Angeles, San Antonio, District 1372, lines 26-29.

5 The 1932 Graham city directory lists his occupation as a cartoonist, though it does not list his place of employment. It is plausible that Hawkins started at Mintz that year.

6 Joe Adamson, interview with Dick Huemer, July 28, 1968, transcription in Recollections of Richard Huemer Oral History Transcript, p. 45.

7 John Canemaker, Walt Disney's Nine Old Men and the Art of Animation, p. 33. In his interview, Hawkins did not clarify his status as an artist working for Disney. Reitherman was hired at the studio on May 21, 1933, so this event might have occurred after.

8 The Film Daily, June 24, 1937, pp. 1 and 3.

9 The Film Daily, October 15, 1937, p. 12.

10 The Film Daily, October 22, 1937, p. 7.

11 John Canemaker, The Animated Raggedy Ann and Andy, p. 85.

12 Kingman Daily Miner, September 2, 1992, pp. 1 and 3.

13 Marriage license of Lovell Burch Norman and Marguerite Estelle Reese, dated June 26, 1938. California, County Marriages, 1850-1952. Courtesy: FamilySearch.

14 The Film Daily, April 30, 1938, p. 2.

15 Milton Gray, interview with George Gordon, January 4, 1977; quoted in Michael Barrier, Hollywood Cartoons, p. 290.

16 Michael Barrier, Hollywood Cartoons, pg. 472.

Hi Devon:

ReplyDeleteThanks for these great posts profiling Emery. You've done quite well in providing citations and I eagerly look forward to future profiles of this quality.

There are a few nits to pick... You misattribute Sid Marcus's films "The Air Hostess" and "The Little Match Girl" as being directed by Art Davis. As with the other films that you correctly attribute to Marcus, these gave Marcus the "Story" credit (relabeled "Direction" on the Color Rhapsodies beginning with "Window Shopping") in their original credits as recorded in the Cumulative Copyright Catalog. Additionally, Davis himself told Michael Barrier and Milton Gray in their first interview with him that Marcus directed "The Little Match Girl" (Mr. Barrier confirmed this to me in an email). Moreover, from examining the films, in terms of style/sensibility they're in line with the work of Marcus and crew rather than Davis; Davis's stuff was quite distinct in its own style by that time. While I can't rule out Davis contributing to "The Little Match Girl" in a co-directorial capacity to some degree, I'm not aware of any evidence establishing that and Leonard Maltin's attribution of it as co-directed in his book doesn't carry much weight with its lack of substantiation.

The IDs of Hawkins' work at Mintz are largely consistent with what I had been picking up on, but I'm pretty sure the footage from near the end of "The Little Match Girl" is actually by another animator who also does, for instance, the closeup of the girl looking around after entering heaven earlier in the picture. I'm not so sure that the bit from "The Air Hostess" with the boy throwing the propeller back on isn't by another animator as well. Also, in "The Foolish Bunny", I'm thinking the initial footage with the teacher conducting the class and the elderly rabbit snoozing is correctly ID'd but later we see him noticeably skinnier; there appears to me to be a change in animator here.

Overall though, I wish more animation-related historical writing elsewhere was up to this standard. Please keep up the good work.

Marcus's credits on AIR HOSTESS and THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL have been corrected now.

Delete