From December 1, 1938, Hawkins was officially on the Disney payroll.1 With his childhood aspirations achieved, he and his wife had their first child, Bruce Lee Hawkins, on June 28, 1939.2 Assigned to the “Duck unit” for director Jack King, Hawkins was credited on the production drafts for several Donald Duck cartoons: The Autograph Hound (1939), Donald’s Dog Laundry, Mr. Duck Steps Out, Put-Put Troubles, Donald’s Vacation, Fire Chief (all 1940), and Timber (1941).3 Based on what the drafts reveal, Hawkins was rarely given long stretches of animation to handle himself. Instead, Hawkins was given just a few of his own scenes and otherwise tasked with making changes to completed sequences whose animators were not available to revise them themselves, usually due to having been shifted onto unrelated feature film productions.

Hawkins’ position at the studio expanded further when he was also given a position in the story department. He would split responsibilities during the working day— half his time developing stories, then back to his animation desk for the remainder. “They took the stuff I turned in and made pictures out of it. It was really material,” Hawkins said. “Situations, like a roadside market and different things that they built pictures out of.”4 A document entitled “Suspended Shorts – Material in Story Library Files,” dated February 17, 1940, mentions several shelved cartoon stories Hawkins submitted or supervised in story sketch form; their working titles are “Donald the Hunter” and “49’er Story.”5

Emery's World War II draft registration card, listing his occupation at Disney.

Hawkins animated on three 1941 Mickey Mouse cartoons directed by Clyde “Gerry” Geronimi, all actually starring Pluto: Canine Caddy, Lend a Paw, and A Gentleman’s Gentleman. Though Hawkins was primarily an animator for theatrical shorts, he remembered that Norm Ferguson, a top Disney animator who became a director in the early 1940s, had intended to give Hawkins a sequence to animate for a feature. This assignment, which he believed was for Dumbo, coincided with “the very day” that the Disney strike started: May 29, 1941. (Hawkins’ Dumbo citation might be in error; Ferguson was a sequence director on that film, but Michael Barrier’s The Animated Man confirms that Dumbo was finished, except for some re-recording of the soundtrack when the strike began.)6

“They said, ‘If you go through that picket line, we’ll never speak to you again.’ Well, I didn’t care, I went out.” Hawkins became one of the 334 striking artists outside of the studio. His ambition to join Disney’s organization seemed different in hindsight; he reflected, “I guess I found it oppressive. I didn’t really feel good about it.” Hawkins’s concerns about Disney extended to some of their production methods. In his animation, he strived to change the usual formula of “fixed walks” with “fixed characters,” exaggerating the actions by pushing and stretching the action further. But Hawkins was unable to accomplish this within Disney’s standard work methods. “I would spend weeks, by their instructions, trying to get something like some other bloke had done. It was just not fun,” Hawkins lamented. One of the prominent strikers, layout man John Hubley, planned to produce an animated film related to the strike, with a crew of other strikers. “I’m the only guy that turned in scenes [for it],” Hawkins said. “Everybody else was talking about it, but nobody did anything.”

Scenes animated by Hawkins at Disney, based on production drafts.

Excerpts: THE AUTOGRAPH HOUND (1939), DONALD’S DOG LAUNDRY (1940), MR. DUCK STEPS OUT (1940), DONALD’S VACATION (1940), FIRE CHIEF (1940), A GENTLEMAN’S GENTLEMAN (1941),

CANINE CADDY (1941), LEND A PAW (1941).

On September 12, 1941, Hawkins was laid off from Disney, just as the strike ended. About a week later, Frank Tashlin was appointed the production supervisor of Screen Gems (a rebranding of Charles Mintz’s studio after Mintz passed away in 1939), which made cartoons distributed by Columbia Pictures.7 Tashlin’s first order of business was to hire many of the former Disney strikers, with Hawkins included. Tashlin, formerly a director, now leaned toward delegating directorial duties to Alec Geiss and Bob Wickersham while finessing the stories and handling the studio’s business activities.

Geiss made a memorable supervisor for Hawkins. When acting out a scene, Geiss would “scream and run up the walls almost. I had a ball because I took the damn scene, and I did it like he acted. I did my best work [at Screen Gems]. I did some things I’m extremely proud of.” In Geiss’s spot-gag cartoon Wacky Wigwams (released February 1942) and Wickersham’s Woodman Spare that Tree (released July 1942), starring the Fox and the Crow, Hawkins’s animation is freed to be wild, as it had been earlier at MGM, liberated from the conventional methods that stifled him at Disney’s.

A few months later, in April 1942, Screen Gems general manager Ben Schwalb was put in charge of the studio’s cartoons, and Tashlin was demoted.8 That same month Dave Fleischer, after leaving his studio in Miami, arrived in California and assumed the title of executive producer at Screen Gems.9 Tashlin continued to supervise the cartoons in some respects but left the studio by June 22.10 These activities seem to overlap with Hawkins’s reinstatement back at Disney on July 13, where he remained for a brief period, leaving on September 4. (As of this writing, it is unknown which Disney productions Hawkins was involved in during this span.)

Selection of Hawkins’ animation at Screen Gems.

Clips: A HOLLYWOOD DETOUR (Tashlin/1942), WACKY WIGWAMS (Geiss/1942), SONG OF VICTORY (Wickersham/1942), DOG MEETS DOG (Geiss/1942), WOODMAN SPARE THAT TREE (Wickersham/1942), TITO’S GUITAR (Wickersham/1942).

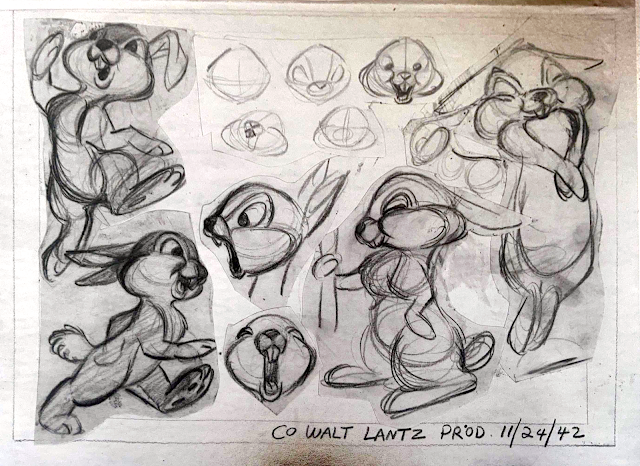

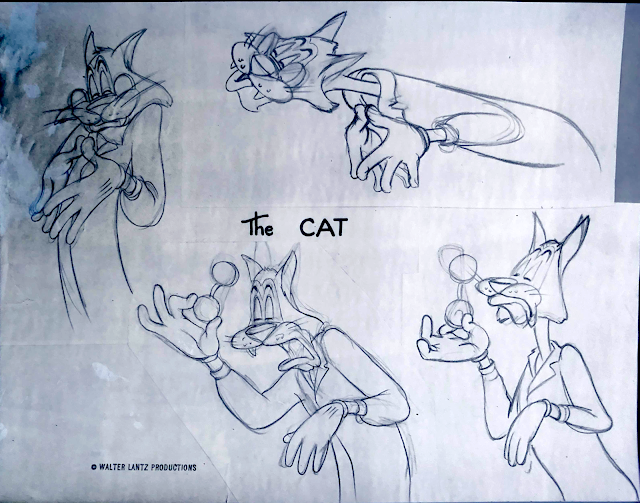

The following month, Hawkins entered Walter Lantz’s studio a second time, now as a more proficient animator. His earliest known work is seen in Swing Your Partner (released April 1943) and The Dizzy Acrobat (released May 1943), both directed by Alex Lovy.11 In late November 1942, Lovy departed to enlist in the Navy, and Lantz needed a director to fill the slot.12 Hawkins teamed with writer Ben Hardaway on The Egg-Cracker Suite (released March 1943), featuring Oswald Rabbit, and Milt Schaffer for Ration Bored (released June 1943), featuring Woody Woodpecker. Directing proved burdensome, as he said: “[I] almost went out of my head. Every night, I’d go home and you know how it feels if you start yelling with a waste basket over your head. I mean that reverberation. That’s what I would have and my face would be hot because all I was doing was talking and it’s not for me.”

At the end of March 1943, James “Shamus” Culhane joined Lantz as the singular new director.13 After animating on Culhane’s first two Swing Symphonies, Boogie Woogie Man (released September 1943) and The Greatest Man in Siam (released March 1944), Hawkins played an essential role in developing Lantz’s top star in The Barber of Seville (released April 1944). Collaborating with character layout man Art Heinemann, Hawkins redesigned Woody into a refined and appealing lead.14 In that same film, Hawkins animated a new opening title of Woody bursting out of a tree stump shouting “Guess who!” and cackling his signature laugh before his body convulses from right to left in a pecking motion. (This opening sequence remained in use on Woody’s cartoons until 1949.) Hawkins animated a few scenes in Barber, but his animation of Woody singing the last movement of Rossini's “Largo al Factotum,” shaving and grooming an Italian customer in a series of rapid film cuts, bookended the most ambitious Lantz cartoon to date.

In November 1943, Dick Lundy was put on the payroll and was promoted as a director in March 1944, working concurrently with Culhane.15 Lantz expected his animators to produce 25 feet of animation a week, a typical figure in many studios that Hawkins had found strenuous. Culhane wrote in his memoir, Talking Animals and Other People, “[Emery] had his own standards of quality and would often throw out a whole day’s work, just after I had assured him that it was a beautiful piece of animation. Emery was never satisfied with any of his work and suffered more agonies of anxiety and frustration than any other animator I have ever met.” Then, one day, Culhane gifted Hawkins with a copy of Kimon Nicolaides' The Natural Way to Draw, a cathartic moment that changed his outlook on drawing.16

Before Hawkins received Nikolaides’ book, he tended to put his pencil to paper with a “soft, light line,” drawing over them with a clean line, but “it was a terrible nervous strain,” as Hawkins recollected. This changed after Hawkins read Nikolaides. “When I started drawing these figures of people, how their figure is shaped and how it bends getting into poses, how the neck and the torso and all that works, it started getting fascinating, and I could see it with [Honoré] Daumier and different artists.” Hawkins filled the back layer of the book with rough drawings, observing lessons in mass, contour, and gesture of the human figure “until I could see it in my sleep.” From thereon in, Hawkins started with either the final or middle drawing, gradually expanding the action to his preference. Meanwhile, Hawkins and his wife brought another addition to their family with another son, Wayne Jeffrey, on June 8, 1944.17

In the relaxed atmosphere of Lantz’s studio, Hawkins was known to administer his share of horseplay to his fellow staffers. Roger Armstrong, a comic book artist who worked briefly at the studio from 1944-45, remembered: “[Hawkins] was a wild man. He’d get up on top of the cubicles, and he’d wait for people to come in from lunch, then he’d leap down on them, screaming with maniacal laughter. A little bit nutty, really, but a funny man.” Armstrong recalled another incident where Hawkins gave animator Pat Matthews a hot-foot, affixing a matchstick to the sole of his shoe, but this failed when the match burned out. The solution: Hawkins emptied a wastebasket filled with crumpled paper around Matthews’s feet and ignited a flame. Armstrong said: “Finally, with that flame roaring around his feet, Pat pulled his feet back, and looked over to see what the hell was going on. As he did so, the guys were busy beating the fire out, because it was beginning to take off.”18

Walter Lantz’s animation staff in 1945. Hawkins is seated in the front row at the far right.

The other artists seated in the front row (l to r): Les Kline, James Culhane, Pat Matthews, and Dick Lundy. Top row: Paul Smith, Grim Natwick, Sidney Pillet, Bernard Garbutt.

Image courtesy: Michael Barrier.

Model sheet from Lundy’s Bathing Buddies (1946), using rough drawings from a sequence animated by Hawkins.

Image courtesy: Van Eaton Galleries.

Scenes animated by Hawkins at Walter Lantz, in production order.

Clips: BOOGIE WOOGIE MAN (Culhane/1943), THE GREATEST MAN IN SIAM (Culhane/1944),

THE BARBER OF SEVILLE (Culhane/1944), JUNGLE JIVE (Culhane/1944), FISH FRY (Culhane/1944), ABOU BEN BOOGIE(Culhane/1944), THE BEACH NUT (Culhane/1944), SKI FOR TWO (Culhane/1944), THE PIED PIPER OF BASIN STREET (Culhane/1945), THE PAINTER AND THE POINTER (Culhane/1944), THE SLIPHORN KING OF POLAROO (Lundy/1945), WOODY DINES OUT (Culhane/1945), CROW CRAZY (Lundy/1945), THE DIPPY DIPLOMAT (Culhane/1945), MOUSIE COME HOME (Culhane/1946), THE LOOSE NUT (Culhane/1945), THE POET AND PEASANT (Lundy/1946), WHO'S COOKIN’ WHO? (Culhane/1946), APPLE ANDY (Lundy/1946),

THE RECKLESS DRIVER (Culhane/1946), BATHING BUDDIES (Lundy/1946), FAIR WEATHER FIENDS (Culhane/1946).

Culhane departed Walter Lantz’s studio by October 26, 1945, which left Lundy as the sole director.19 Hawkins left at the same time; he had been hired at Disney once again, starting work on October 29. Again, he worked in Jack King’s “Duck unit,” credited with three Donald cartoons: Donald’s Dilemma (released July 1947), Wide Open Spaces (released September 1947), and Donald’s Dream Voice (released May 1948). His scenes in Dilemma and Dream Voice drastically improved from his earlier work for Disney. In Dilemma, Hawkins animated Daisy’s psychological self-torture over her withdrawal from the amnesiac Donald, now a famous crooner. Dream Voice casts Hawkins with a remarkable turn in the Duck’s career: Donald speaking like a sophisticated (un-ducklike) gentleman with the aid of voice pills, and his ecstatic reactions to discovering how his voice has changed.20

However, the studio suffered financial hardships when the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild demanded a 25 percent increase in base minimum wages, which Disney could not provide.21 After the union threatened to strike, raises were dispensed to the employees, but the studio was forced to lay off a total of 459 employees the same week.22 With Jack King’s directorial unit dissolved, Hawkins was off the Disney payroll on July 26, 1946. Hawkins had animated at least a few scenes in The Trial of Donald Duck (released July 1948), King’s last completed cartoon as a director for Disney.

In approximately August 1946, Hawkins was hired at Warner Bros. as an animator under director Art Davis.23 As an old colleague from Charles Mintz’s studio, Davis boosted Hawkins’s work and advocated his hiring. Starting with Doggone Cats (released October 1947), Hawkins’s animation for Davis was at its most uninhibited, well-suited to the absurdist sensibilities of Davis’ cartoons at Warners. These facets are highly apparent in Two Gophers from Texas (released January 1948), in which Hawkins animates the opening scenes of a brash, theatrical dog, histrionically describing his keen interest in the conquest of “the tangy zest of wild game” to the audience. Hawkins handled few scenes of the Goofy Gophers, instead using the dog as a powerful vehicle for rampant lunacy.

Hawkins did not last long in Davis’s unit after joining Warners. Around November 1947, the studio implemented an economic decision to downsize the directorial units in the animation department from four to three.24 Since Davis did not share the seniority as principal directors Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones, and Bob McKimson, his unit disbanded. Ultimately, Hawkins was shifted to McKimson’s unit while intermittently animating in the Jones and Freleng units. Among the highlights of Hawkins’s assignments are noteworthy musical sequences: Daffy’s introductory song in Boobs in the Woods (released January 1950), the titular number in the Bugs mock-biography What’s Up Doc (released June 1950), the first half—and finale—of the prolonged square-dance in Hillbilly Hare (released August 1950), and Bugs disguised as a Spanish “señoriter” in Rabbit of Seville (released December 1950).

Excerpts of scenes animated by Hawkins for Warner Bros., all directed by Art Davis. These are listed in production order.

Clips: DOGGONE CATS (1947, #1054), THE STUPOR SALESMAN (1948, #1058), PORKY CHOPS (1949, #1061), TWO GOPHERS FROM TEXAS (1948, #1066), WHAT MAKES DAFFY DUCK(1948, #1069), A HICK, A SLICK, AND A CHICK (1948, #1073), RIFF RAFFY DAFFY (1948, #1079), BONE SWEET BONE (1948, #1082), BOWERY BUGS (1949, #1085), DOUGH RAY ME-OW (1948, #1088), ODOR OF THE DAY (1948, #1093), HOLIDAY FOR DRUMSTICKS (1949, #1096), BYE BYE BLUEBEARD (1949, #1101).

Hawkins continued to nurture his creativity while at Warners, participating in art classes held in the studio. “I worked around people like Paul Julian [Freleng’s background painter]. They’d give us projects and we’d go home and paint them.” Within a decade, he had worked in nearly every animation studio that produced theatrical cartoons on the West Coast. Hawkins again felt confined and wanted an escape. “I had gotten to the feeling that I couldn’t quite stand people being hit over the head and making ‘takes’ in the shorts,” he said. Television became a burgeoning medium in American households, with many studios forming in New York specializing in animated commercials. This salvation delivered a promising change in his path, as he stated, “Commercials gave me the opportunity to go my own way, to be creative.”25 Hawkins relocated to New York in early 1950.26

Another selection of scenes animated by Hawkins at Warner Bros., listed in production order. Many of the cartoons are directed by Bob McKimson, with exceptions noted.

Clips from: HURDY-GURDY HARE (1950, #1105), A HAM IN A ROLE (1949, #1106), HOMELESS HARE(Jones/1950, #1107), BOOBS IN THE WOODS (1950, #1110), STRIFE WITH FATHER (1950, #1111), WHAT’S UP DOC? (1950, #1114), THE LEGHORN BLOWS AT MIDNIGHT (1950, #1116), AN EGG SCRAMBLE (1950, #1119), 8 BALL BUNNY (Jones/1950, #1123), DOG GONE SOUTH (Jones/1950, #1126), ALL ABIR-R-R-D (Freleng/1950, #1127), GOLDEN YEGGS (1950, #1128) HILLBILLY HARE (1950, #1130), TWO’S A CROWD (Jones/1950, #1134), CANARY ROW (Freleng/1950, #1136), RABBIT OF SEVILLE (Jones/1950, #1138), STOOGE FOR A MOUSE(Freleng/1950, #1139), A BONE FOR A BONE (Freleng/1951, #1155), EARLY TO BET (1951, #1159), LEGHORN SWOGGLED (1951, #1162), FRENCH RAREBIT (1951, #1167), LOVELORN LEGHORN (1951, #1169), SLEEPY-TIME POSSUM (1951, #1172), THE PRIZE PEST (1951, #1188).

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 David R. Smith (founder of the Walt Disney Archives), private message to author, May 6, 2013. Further information about Hawkins’s start and end dates originate from this exchange.

2 California Birth Index, 1905-1995. Courtesy: Ancestry.

3 With the exception of Donald’s Vacation, Fire Chief, and Timber, these documents of Donald and Mickey cartoons have been shared in Hans Perk’s A. Film LA blog from his personal collection.

4 David Gerstein, private message to author, June 29, 2022. Hawkins’s mention of a “roadside market” alludes to a proposed late 1930s short, “Donald’s Roadside Market,” which was judged to have too much material in it for a single short. It was split into different farm cartoons, featuring Donald’s battle with a rooster for eggs (Golden Eggs, 1941), with a gopher for melons (Donald’s Garden, 1942), with a horsefly for milk (Old MacDonald Duck, 1941), and with a bee for honey, with a car radiator functioning as a hive (Honey Harvester, 1949).

5 This document was sold in a lot auctioned at Blacksparrow Auctions on July 18, 2014, listed as Item #41: Collection of 1930s Walt Disney Studios Production Documents.

6 Michael Barrier, The Animated Man, p. 176.

7 The Film Daily, September 19, 1941, p. 10.

8 Variety, April 8, 1942, p. 27; referenced in Michael Barrier, Hollywood Cartoons, p. 380.

9 Motion Picture Herald, April 25, 1942, p. 28.

10 The Animator (Screen Cartoonists Guild, Local 852 newsletter), June 22, 1942. This document was sold on December 2, 2013, at Heritage Auctions, for Profiles in History: December 2013, Auction #997011, Lot #1228: Unusual Collection of Disney Studio Memorabilia from the Estate of Clarke Mallery.

11 Swing Your Partner (prod. C-8) model sheet, dated October 7, 1942. Private collection.

12 The Egg-Cracker Suite (prod. C-10) model sheets, dated November 24, 1942. Courtesy: UCLA Special Collections, Walter Lantz Animation Archives, 1929-1972. Lovy was off the Lantz payroll a few days earlier, on November 18.

13 Lantz personnel notes compiled by Joe Adamson. Courtesy: Michael Barrier.

14 Shamus Culhane, Talking Animals and Other People, pp. 262-263.

15 Lantz personnel notes compiled by Joe Adamson. Courtesy: Michael Barrier.

16 Culhane, p. 263.

17 California Birth Index, 1905-1995. Courtesy: Ancestry.

18 Roger Armstrong, audio letter to Michael Barrier, May 9, 1975; published as “Essays: Life at Lantz, 1944- 45” on Barrier’s official website, March 20, 2011.

19 Lantz personnel notes compiled by Joe Adamson. Courtesy: Michael Barrier.

20 JB Kaufman, private messages to author, November 17, 2020, and June 4, 2021.

21 Variety, July 31, 1946, p. 8.

22 Letter from Disney concept artist Sylvia Holland to Glenn Holland, September 3, 1946; referenced in Didier Ghez, They Drew As They Pleased, Volume 2: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Musical Years (The 1940s – Part One), p. 93. That total number of employee layoffs is listed in Michael Barrier, Hollywood Cartoons, p. 388.

23 Bea Benaderet's dialogue track for Doggone Cats (prod. #1054) was recorded July 13, 1946, almost two weeks before Hawkins's layoff from Disney. Davis's next cartoon in production, The Stupor Salesman (#1058), had its voice recording session on August 17, 1946. WB Music Department, Jack Warner Collection; USC Cinema-TV Library. Courtesy: Keith Scott.

24 Stan Freberg recorded his dialogue for A Ham in a Role (prod. #1106) on November 15, 1947. Originally slated with Davis as the director (with Sid Marcus newly hired as his writer), McKimson took over the cartoon after the Davis unit dissolved. WB Music Department, Jack Warner Collection; USC Cinema-TV Library. Courtesy: Keith Scott.

25 "Taos Cartoonist Animates Life." The Taos News, January 7, 1982.

26 Hawkins's last on-screen credit for Warners was on Who's Kitten Who; the dialogue track session occurred on January 7, 1950. However, the production draft for the cartoon shows no footage assigned to him, an indicator he might have left during mid-production. WB Music Department, Jack Warner Collection; USC Cinema-TV Library. Courtesy: Keith Scott. The March 1950 issue of Top Cel reported Hawkins had already settled on the East Coast. Courtesy: Richard O' Connor.

The Lantz clip reel alone had more entertainment value than an entire season of any modern-day cartoon series.

ReplyDeleteThis is just excellent, Devon. Hawkins certainly deserves this level of attention, and you've done him proud.

ReplyDeleteThe "Screen Gems" name pre-dates Mintz's death. It was the name picked for the combined Winkler (West Coast) and Mintz (ex East Coast) studio.

ReplyDeleteSee Variety, Dec. 8, 1931, pg. 11.

Thanks, Yowp!

DeleteLOVE this blog, Devon - you are doing fantastic work! Hope you will get the opportunity to include these posts and your Cartoon Research posts into a book on animation history.

ReplyDelete