1950 Halo Shampoo commercial Hawkins animated for Culhane's TV studio.

By July 1950, Hawkins migrated to Transfilm on 45th Street, where Jack Zander—once an animator on “The Captain and the Kids” at MGM—served as the head of the animation department.1 Hawkins remained with Zander until he returned to California in November.2 It is uncertain whether Hawkins’ quick migration—between three studios in a single year—came about due to his feeling personally unfulfilled, or simply because the ad studios didn’t have enough work to keep him busy, reliant as they were on the rapidly-shifting needs of clients.

In the first half of the decade, Hawkins frequently worked with John Sutherland Productions, which was then releasing industrials sponsored by large corporate organizations: Harding College (The Devil and John Q [1952] and Dear Uncle [1953]), The New York Stock Exchange (What Makes Us Tick [1952]), General Electric (A is for Atom [1953]), the United States Chamber of Commerce (It’s Everybody’s Business [1954]), and the Albert B. Sloan Foundation (Horizons of Hope [1954]). Between assignments for Sutherland, Hawkins moonlighted on a Ford commercial with animator Cecil Surry at a studio space owned by Ade Woolery and Mary Cain, formerly of UPA.3 John Hubley designed the Ford spot; a former director at Screen Gems in the early forties, Hubley had been fired from UPA after he refused to cooperate with HUAC (House of Un-American Activities) for his communist stance in May 1952.4 Hawkins, a strong advocate for worker’s rights himself, became involved in union activities for the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild, and was elected as a trustee to Local 852. Hawkins held this position until 1952, when the Guild appointed him as conductor.5

Main title card featuring Dibujos Animados' characters: the donkey Burrito Bonifacio, Gallito Manolin the rooster, and the treacherous crow Armando Rios, who reflected communist ideology.

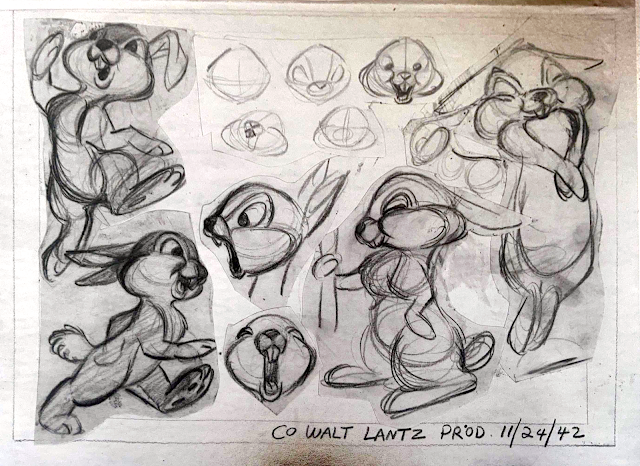

The American government’s crusade against communism led to films with a propagandist slant, which often included Sutherland’s films. In December 1952, an animation studio called Dibujos Animados, S. A. (translating to “animated cartoons”) opened in Mexico under the auspices of Richard K. Tompkins, representing the USIA (United States Information Agency).6 Hawkins decided to work for this studio, relocating to Mexico by April 1953.7 Pat Matthews, Hawkins’s cohort from Lantz, also left UPA to try his luck there. Dibujos Animados, S. A. produced twelve cartoons with anti-Communist themes, but only one was theatrically released; Manolín Torero (Manolin the Bullfighter) was screened at the Alameda movie theater in Mexico City on July 1, 1954.8 Hawkins directed the cartoon, with Matthews as part of the animation crew. While it bears his stamp in character design and animation, Hawkins’s third stint as a director fails on a technical level; camera errors abound throughout the film.

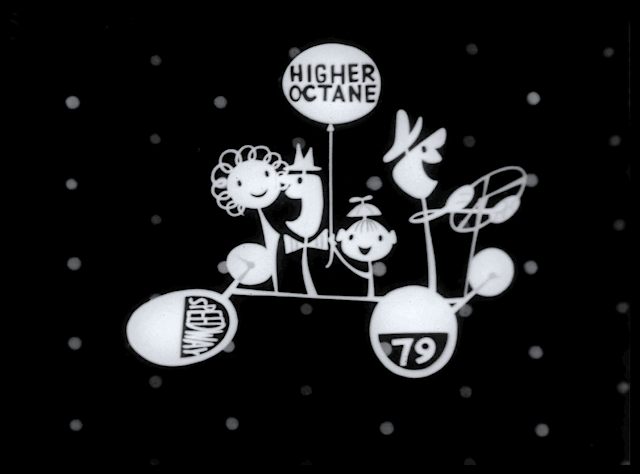

In 1954, John Sutherland opened a second operation in New York on 28th and Fourth Avenue, Sutherland Television Films, to develop industrials and commercials.9 Hawkins went with Sutherland to his New York offices in September for two months, after which he returned to California in November.10 By May 1955, Hawkins received work on commercials for John Hubley at Hubley’s new commercial studio, Storyboard.11 Hubley’s lively commercial for Speedway 79 Gasoline, using a jazz version of “Dem Bones” for its jingle, displayed Hawkins (with animator Arnold Gillespie) adapting significantly to the era’s stylized modern approach to animation design.

The following year, Hawkins animated for Playhouse Pictures, a commercial studio founded by Ade Woolery, while working on at least one industrial for Sutherland (Working Dollars [1956] for the New York Stock Exchange). Meanwhile, Hubley closed Storyboard's West Coast offices in July, transferring services to New York.12 Earning numerous awards for his commercials, Hubley directed the first ad campaign for Maypo breakfast cereal, which became a vast sales booster when it aired on northeast television stations in September.13 As animated by Hawkins, little Marky is obsessed with his beloved, oversized cowboy hat; Marky’s father coaxes him to take off his hat and eat his bowl of the maple-flavored oat cereal. Inadvertently, father’s persuasions lead the spoonful into his own mouth; after savoring the maple flavor, Marky’s father claims the cereal bowl for himself. His son turns his attention away from his cherished hat, crying, “I want my Maypo!” Hawkins might have handed his assignment to Hubley via mail correspondence (“[I] worked by mail for him for a couple of years,” he mentioned.) In November, Hawkins left for New York to join Storyboard.14

From January to March 1957, with Ed Smith as his assistant, Hawkins involved himself with The Adventures of an *, the first collaborative short by Hubley and his wife, Faith Elliott, commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum.15 As the sole credited animator, Hawkins helped utilize innovative techniques in Hubley’s film, animating figures using a “wax-resist” method, drawing the figures with wax, and adding a touch of watercolor to produce a resisted texture.16 After completing his work on the film, Hawkins traveled back to Los Angeles, where Hubley entrusted him in a different capacity at Storyboard: the 1957 yearbook edition of Television Age magazine lists him as Storyboard’s West Coast manager.17

Hawkins continued his association with Storyboard and John Sutherland Productions while devoting his time to television commercial workshops as a freelancer: Playhouse Pictures, Le Ora Thompson Associates (formed by Playhouse's sales director Leora Thompson and Carl Urbano), and Fine Arts Productions (supervised by former Disney layout man John Wilson).18 For Storyboard, Hawkins’s credits include Hubley’s painterly love story The Tender Game (1958), John and Faith’s third independent film together, and the opening title sequence for the short-lived CBS anthology series The Seven Lively Arts (1957-58).19 At Sutherland, Hawkins served as an animator for Fill ‘Er Up (1959), sponsored by DuPont, and Rhapsody of Steel (1959), the studio's most extravagant film about man's precious metal, funded by US Steel. In addition, Hawkins found love with a woman who worked at Sutherland's, Odette Alice Flood, whom he later married on April 20, 1959.20

1959 also inaugurated Hawkins’s arrangement to regularly send his commercial work through the mail from California to Pelican Films, Jack Zander’s new studio in New York. Among his jobs for Pelican was a series of 60-second spots promoting Jax Beer, written and voiced by the improvisational comedy act Mike Nichols and Elaine May. One example, animated by Hawkins and Bob Perry, involves a talking kangaroo (Nichols) requesting a cold beverage from a human bartender (May). First aired in July 1960, it garnered an award for best advertisement in the Beers and Wines category at the Second Television Commercials Festival in 1961.21 Then, in 1962, Hawkins left the West Coast indefinitely for New Mexico, settling with his wife in Santa Fe. The following year, Emery and Odette purchased a ranch house on La Lorna in Taos County, a town they passed during their travels on their honeymoon.22

TV commercials animated entirely or partly by Hawkins from the late 1950s to the early 1960s.

Bank of America (Storyboard, c. 1955), Speedway 79 Gasoline (Storyboard, 1955 – co-animated with Arnold Gillespie), “The Lion and the Mouse” (Storyboard, 1957, co-animated with Art Babbitt), Desoto Painter (Playhouse Pictures, c. 1956 – co-animated with Bill Melendez), Stop in the Sign of 76 (Playhouse Pictures, 1956, co-animated with Herman Cohen), three Maypo spots (Storyboard, 1956-57), Desoto spot (Le Ora Thompson Associates, 1958), Falstaff “Punt” (Storyboard, 1959), Kingsway Shoes (unknown studio, c. late 1950s, co-animated with Phil Duncan), four Jax Beer spots (c. 1960-61). Thanks to Mike Kazaleh for lending a few of these spots from his collection.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Hawkins settled into a routine of working remotely from his studio in Taos. After maintaining his livelihood in major American cities, he felt serenity in his new abode. “Beautiful blue skies, clean air, and sweet water, and quiet at night—a real nice combination; lots of room and our house is an old house with big rooms, and it's kind of private, and it's very nice. Very lovely place.”

Considered a reliable asset to longtime colleagues, including Jack Zander at Pelican, Hawkins accepted different projects from producers Jerry Fairbanks (We Learn About the Telephone [1965, sponsored by Bell Telephone])23 and John Hubley (A Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass Double Feature [1966]). Later, he moonlighted on commercials for Summer Star Productions, a studio founded by Mordicai “Mordi” Gerstein; Hawkins had previously animated on Gerstein’s short film A Nose (1968) produced at Pelican.24 Hawkins’ association with Jack Zander prevailed when in 1970, Zander’s Animation Parlour opened in New York, with Hawkins hired as a freelancer.25 Bill Melendez, a fellow animator of Art Davis’s unit at Warners and a top animator/director for Playhouse, enlisted Hawkins to work on at least two films with the Peanuts characters, Play It Again, Charlie Brown (1971) and the feature Snoopy Come Home (1972). Apart from animation, Hawkins engaged himself in the New Mexican art scene, showcasing his paintings at cultural events, often with the backing of the Taos Art Association.26

On February 20, 1975, Richard Williams, a producer-director acknowledged for his work on commercials at his studio in London and an Oscar win for his 1971 adaptation of A Christmas Carol, set forth his plans for production on Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure at a meeting with The Bobbs-Merrill Company (then the Raggedy Ann rightsholder), with Broadway producers Richard Horner and Lester Osterman in attendance. During the meeting, Williams mentioned Hawkins’s name as part of the selected group of directing animators assigned to the feature.27 In June 1975, Hawkins traveled by train from Taos to New York to appear at a summit meeting with the key animators. The Raggedy Ann vocal performances, and Joe Raposo’s musical score, had been recorded a month prior; now Williams and his animators held story conferences to establish the personalities of their designated characters.28

Mike Sanger, a freelance animator on the feature (uncredited), socialized with Hawkins and frequently visited his Taos studio while Emery labored on his scenes. Paraphrasing Mike's recollections, Mark Kausler described the Taos studio as “a real tropical rat's nest.” Mark continues, “Emery was almost always completely disorganized but became instantly sharp when he was animating.” Darrell Van Citters accompanied Mike during one visit to Emery's home studio. Besides the cowboy boots catching his attention, he noticed “[Emery’s] forearm was black from pencil lead because of the soft pencils he used and the 16-field paper he was working on [animating the Greedy].”29

Between June 1975 and January 1976, Hawkins worked the slowest of all the directing animators, rattling the Raggedy Ann producers. As it happened, he reworked the opening portions of the Taffy Pit sequence three times before finding what he considered the Greedy’s essence.30 The laborious sequence required its characters to be drawn on several action levels: Raggedy Ann, Andy, and the Camel with the Wrinkled Knees on one level, the rolling waves of the Taffy Pit—with its mounds of delectable confections and sweets—on another, and the Greedy on the third. With Dan Haskett as Hawkins’ key assistant animator, cleaning up his drawings, an average of only six cleanups could be completed each day, given the meticulous detailing of the sketches and the necessity of maintaining the consistency of each action level. In a rare instance, one day found Dan surpassing his usual quota with ten cleanups instead of six.31

The summer of 1976 saw pencil tests from the directing animators being screened in New York bi-weekly. Emery’s scenes met with unanimous applause from Raggedy Ann’s creative staff after each presentation. The renowned animator Art Babbitt found the Taffy Pit sequence masterful and a “tour de force.” Babbitt said to John Canemaker, “I sent [Emery] a fan letter, the first one I’ve ever sent in my life to anyone, including Mary Pickford.”32 Hawkins animated the introduction of the Greedy and the entire song sequence, leading up to the battle in the Taffy Pit, amounting to five minutes of screen time. In a desperate rush to expedite the production in October 1976, Hawkins was taken off the project, with animators Art Vitello and John Bruno inheriting the remainder of the sequence. Keeping a watchful eye on his character, Hawkins sent a list of proclamations to Vitello and Bruno as a guide:

“Thou shalt not feel that the Greedy has а distinct anatomy. Не is а bag of parts—one big bag of opportunities. Lumps rise and turn into hands. Hands rise and turn into lumps. His dialogue is a flatulent bubble-up. Generally, there are three waves getting darker as they recede. I try to make the waves relate to main Greedy action. It's widescreen, so I've tried to make it look like a three-ring circus, rather than just one ring at a time.” 33

The Taffy Pit sequence from Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Musical Adventure.

Sadly, Hawkins soon developed Alzheimer’s disease, forcing him to retire from the business. From September 15-29, 1988, the 21st International Tournée of Animation organized a benefit for the ailing animator in California, screening animated films in theaters from Encino, South Pasadena, and Newport Beach.36 Unfortunately, he passed away in Taos a few months later, on June 1, 1989. After Hawkins’s death, his peers extolled his work in reverence. In an interview with Michael Barrier nearly two years later, Corny Cole stated that besides Bill Tytla, Emery “is, to me, the greatest animator who ever lived.”37

In his instructional book The Animator’s Survival Kit, Richard Williams immortalized animation techniques and sage advice from Hawkins. As Hawkins once said to Williams, “The only limitation in animation is the person doing it. Otherwise, there is no limit to what you can do. And why shouldn’t you do it?”38

Thanks to Jerry Beck, David Gerstein, Mark Kausler, Keith Scott, Mark Mayerson, Don M. Yowp, Frank M. Young, Dan Haskett, Dean Yeagle, and John Canemaker for their help and encouragement. Special acknowledgment to Thad Komorowski for transcribing and sharing John Canemaker's interview with Hawkins on this blog.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Top Cel, July 1950. Courtesy: Richard O’Connor.

2 Top Cel, November 1950. Courtesy: Richard O’Connor. Hawkins is listed in state census records on both coasts during 1950. The New York census, dated April 17, lists him rooming at a residence owned by Lillian Stockley, with his occupation listed as a cartoonist for advertising. 1950 US Federal Census, New York, enumeration district 31-350, lines 19-21. The 1950 Los Angeles census lists Hawkins, his wife Mary, his two children, Bruce and Wayne, and Jay Macwilliam (listed as “aunt”) residing in Los Angeles. Since the LA census records have no enumeration date, it is hard to discern when the Bureau compiled its data. 1950 US Federal Census, Los Angeles, enumeration district 66-142A, lines 4-8.

3 Adam Abraham, When Magoo Flew, p. 131; sourced from Ade Woolery, interview by Michael Barrier, September 9, 1986.

4 Ibid; Michael Barrier, Hollywood Cartoons, p. 534.

5 1950 Film Daily Year Book, p. 908; 1951 Film Daily Year Book, p. 833; 1952 Motion Picture Production Encyclopedia, p. 553.

6 Juan Manuel Aurrecoechea, “The Second Conquest,” referenced in Luna Córnea magazine, no. 20, p. 231.

7 The April 1953 edition of Top Cel mentioned Hawkins embarking on a “Mexican venture.” Author’s collection.

8 Giannalberto Benndazi, Animation: A World History, Volume 2: The Birth of a Style - The Three Markets, p. 91.

9 The April 1954 issue of Top Cel mentions a new West Coast studio, Sutherland Television Films, forming in New York. Author’s collection.

10 Top Cel, September 1954 and November 1954. Author’s collection. The October 6, 1954 issue of The Hollywood Reporter reported Hawkins’s hiring at Sutherland’s New York studio, as well.

11 Art Director and Studio News, vol. 7, no. 2 (May 1955), p. 40.

12 Motion Picture Daily, June 20, 1956, p. 2.

13 Scott Bruce and Bill Crawford, Cerealizing America: The Unsweetened Story of American Breakfast Cereal, p. 158.

14 Top Cel, November 1956. Author’s collection.

15 Top Cel, January 1957; Top Cel, March 1957. Courtesy: Howard Beckerman.

16 Michael Barrier, interview with John Hubley, November 26, 1976; published on Barrier’s website.

17 Television Age, vol. 4, issue 12, (undated) 1957, p. 304.

20 California, US, Marriage Index, 1949-1959; The Taos News, June 2, 1977. My research has failed to turn up documentation regarding the divorce, separation, or passing of Hawkins’ first wife. Any information is appreciated.

21 The 1961 American TV Commercials Festival Award Winners program (May 4, 1961), p. 25; Art Direction, vol. 13, no. 5 (August 1961), p. 33.

22 The Taos News, April 25, 1963, p. 3.

23 Mike Kazaleh, comment on Michael Sporn’s blog, October 15, 2009.

24 Television/Radio Age, vol. 18, no. 11 (January 11, 1971), p. 49.

25 The August 10, 1970 edition of Television/Radio Age magazine, p. 36, and its April 5, 1971 issue, p. 38, mentioned Zander hiring Hawkins exclusively. Contrarily, Dean Yeagle, an animator and director at Zander’s Animation Parlour, said Hawkins worked there as a freelancer. Dean Yeagle, phone conversation with the author, August 3, 2022.

26 “Sixteen Taos Artists In 1965 Fiesta Biennal.” The Taos News, August 5, 1965, p. 6; “Art Auction Special TAA Ball Feature.” The Taos News, November 23, 1967; The Taos News, December 13, 1972; The New Mexican Sun, December 17, 1972, pp. 2 and 20.

27 John Canemaker, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, p. 125.

28 Ibid, p. 145.

29 Mark Kausler, e-mail message to author, July 6, 2022. Darrell Van Citters, e-mail messages to author, June 24, 2019, and July 23, 2022.

30 John Canemaker, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, p. 202.

31 Dan Haskett, phone conversation with author, July 21, 2022.

32 John Canemaker, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy, p. 193.

33 Ibid, p. 203.

34 The Taos News, January 7, 1982.

35 Ibid.

36 The Los Angeles Times, September 15, 1988, pp. 6 and 8.

37 Michael Barrier, interview with Corny Cole, February 23, 1991; published on Barrier’s website.

38 Richard Williams, The Animator’s Survival Kit, p. 26.